Uru Eu Wau Wau – Land in dispute

Pulitzer Center / InfoAmazonia

Brazil, 2019

In Rondônia, the Indians are under siege. It is not just an expression. Open a map and try to locate the Brazilian state to the northeast of the border with Bolivia: decades of deforestation have left indigenous lands as the last green spots. These lands are the source of the rivers that run through the state. These are the forests several ethnic groups, some of them reduced to a few hundred survivors, call home.

These lands are coveted today for their timber, their minerals, their “market value”. Within this besieged area not only is nature being decimated, but indigenous communities are increasingly cornered. The invasion of their lands using fake documents (a practice called ‘grilagem’ in Brazil) and illegal logging are the crimes that are fostering this division of indigenous lands. The territories inhabited by the Karipuna and Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau peoples are being attacked from different directions.

Support for this reporting was made possible by the Rainforest Journalism Fund, in association with the Pulitzer Center.

Grantees Gustavo Faleiros and Fábio Nascimento’s multi-media reporting for InfoAmazonia exposes the indigenous communities’ battles under the continued invasion. Also available in Spanish and Portuguese.

As if we were watching a documentary about hordes of barbarians assaulting Rome, on a trip to Rondônia we witnessed constant invasions and threats to indigenous communities.

Imagine a game: the board is called Rondônia and the objective is to place all the pieces inside the last green islands of forest. The pieces are land grabbers and loggers. They move forward. In this task, they have the support of local politicians, as well as the House of Representatives and the Senate. Public officials and civil society try to prevent these invasions, but they are also threatened.

The Karipuna and Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau fight on. They have resisted for decades, but now it’s different. With the new president, Jair Bolsonaro, the war against indigenous territories has already been declared.

Invasions in indigenous territories in Rondônia are not new. The Karipuna and the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, who remained uncontacted until the 1970s, have lived ever since in a constant struggle to keep their land protected.

The legal status of both reservations continues to be questioned by outsiders, although they have been recognized and protected by presidential decrees. At the local level, rural landowners dispute the boundaries of the indigenous lands, arguing the existence of demarcation errors supposedly proven by old (or fake) documents. On a higher political sphere, mayors and even national Congressmembers defend proposed reductions of their territories. Both groups support each other with the discourse that there is “too much land for too few indigenous persons”.

Data from Catholic Church organizations that since the 1980s have monitored episodes of violence in the countryside, such as the assassination of leaders and threats to communities, reveals the intensification of this struggle.

According to the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI), since 2016 there have been eight episodes of invasion to steal wood and open new clearings within the Karipuna indigenous territory. In the case of the Uru-eu-wau-wau, since 2012 there have been four recorded attacks.

The dismayed chieftain

In September of last year, André disappeared. He was hunting in the jungle with his relatives when he decided to personally verify the presence of invaders inside the land of the Karipuna. He did not come back.

Already knowledgeable of the presence of loggers in their lands, they feared the worst: the chieftain had perhaps run into the invaders. As head of the village of Panorama, the only remaining Karipuna community, André had already suffered threats for his reports denouncing illegal logging and land grabbing within indigenous land.

For several days his cousins searched for him in the bushes bordering the Jaci Paraná River. They returned home that night without news. The chieftain’s mother, Katsiká, usually talkative and smiling, was heartbroken. Her other son, Adriano, also a leader among the Karipuna, had spoken at the United Nations headquarters in New York three months before about the imminent risk of an attack on their indigenous community.

At the end of the third afternoon, André was found. He was staggering along a river bank after having walked through the jungle for 72 hours, without any food. It was a case of disorientation. The landscape of felled trees confused the chieftain, who was no longer able to find his way. Concerned by a face-to-face encounter with the loggers, he had made countless detours trying to get home.

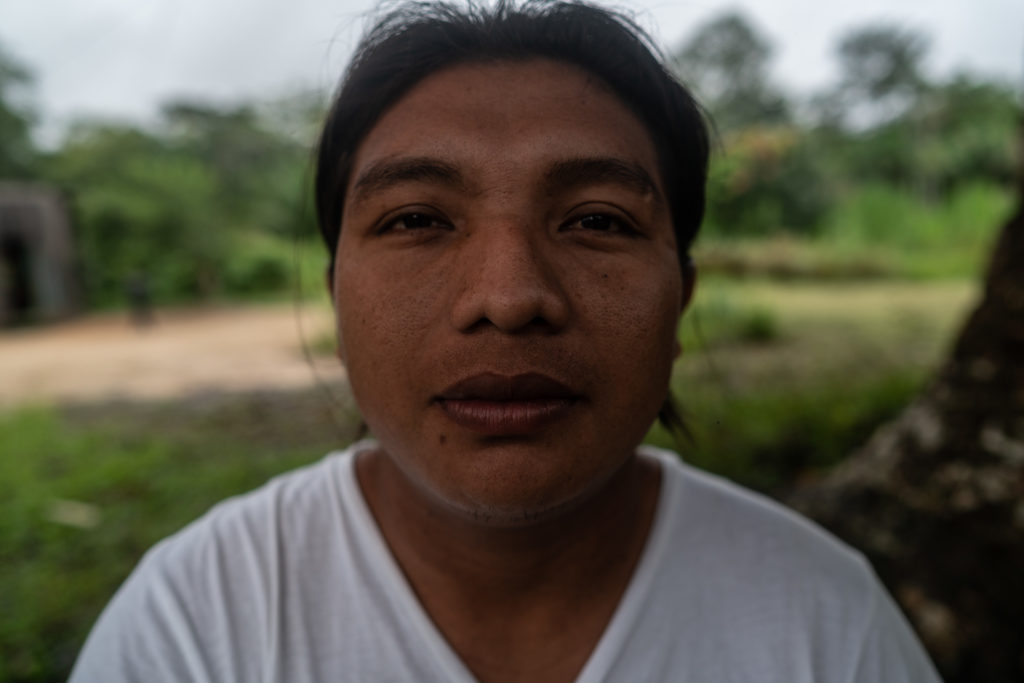

When André received us in February in Panorama village, he recounted the episode without fanfare. For a 26-year-old man, the chieftain’s countenance is grave and rather unsmiling. The responsibility of being the head of the village seems to weigh on him. “I no longer have inner peace” he said. The threats started when he became chief, just a year ago. “I thought I’d give up, get out of here. However, I thought about my mom and my family.”

The boy chieftain and the warrior uncle

Bahira will one day be the cacique, or village chief. No one knows when, but as a young prince, his future is certain: he has already been chosen to lead the village. Today his father Taroba is the chieftain.

Bahira is the youngest of four children. In the village of Upper Jamari, he lives with his father, grandmother, three sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins, and a nephew, Thallison, a one-year-old baby who affectionately clings to the adults’ legs.

Eleven-year-old Bahira is the person who fishes in the village. The white waters of the stream bordering their six wooden huts are full of slender piaba fish. He is also the designated shepherd for the six bulls owned by his community. Early each morning he milks their cows to bring milk to his family.

The future chieftain goes to the school located next to the village’s health center. He is the only child of his age there, although more children his age live in other small villages of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indians. But they are miles away.

The six existing Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau villages are spread out in a territory of 1.8 million hectares. There are also three villages inhabited by Amondawa indians and three isolated or uncontacted indigenous groups.